13.1 Introduction to Partial Differential Equations

We have previously discussed a lot of linear algebra and complex analysis, and we have seen how these topics are useful in physics. In this section, we will introduce the topic of partial differential equations (PDEs), which are equations that involve functions of multiple variables and their partial derivatives. PDEs are ubiquitous in physics; almost every field of physics uses PDEs to describe physical phenomena. In electrostatics, we have Poisson's equation (in Gaussian units)

and in electrodynamics, we have Maxwell's equations

The wave equation

is used to describe wave propagation, and the Schrödinger wave equation

is used to describe quantum mechanical systems.

Table of Contents

Separation of Variables

The first step in solving a PDE is to find a way to reduce the problem to a simpler one. One common technique is to use the method of separation of variables, which involves assuming that the solution can be written as a product of functions, each depending on only one of the variables. We typically assume that the solution can be written as

where

The temporal component is usually a first or second order derivative, so most of our PDEs will look like

So we have, after separating variables,

We can then divide both sides by

As the left-hand side depends only on the spatial coordinates and the right-hand side depends only on time, the only way this can be true is if both sides are equal to a constant, which we will denote by

Notice that the time-dependent part of the equation is a first or second order ODE. The spatial part reduces to a PDE of the form

Generally, our expression for

where

And rewriting

We have a homogeneous PDE, which we typically solve using further separation of variables. The rest of these sections will be devoted to separation of variables in different coordinate systems.

Separation of Angular Variables

Define the momentum operator

The angular momentum operator is defined as

The commutation relations for the angular momentum operator are given by

The reason we are interested in the angular momentum operator is that it is dependent only on the agular variables

To proceed, we need to symmetrize the terms (so that we can collapse them back into a dot product). Therefore we use the commutation relations to write

which simplifies to

Finally, substituting back

Rearranging this expression, and noting that

So we have two important results here; first is a coordinate-independent expression for the Laplacian operator in terms of the angular momentum operator, and second is the expression for the Laplacian operator in spherical coordinates:

Going back to our homogeneous PDE

Let's now perform further separation of variables by assuming that

Assuming, once again, that

(See the appendix for a justification of this step.)

Letting the first term be

The second equation is an ODE for the radial part

Eigenvalues of L² in Abstract Space (Ladder Operators)

Let's consider an abstract vector space where a ket

Since

Recall that a degenerate eigenvalue is one that corresponds to multiple linearly independent eigenvectors. In order to distinguish between these eigenvectors, we need to find another operator that commutes with

Anyways we have

where

In order to find the possible values of

and they are Hermitian conjugates of each other, i.e.,

Since

To verify that ladder operators do indeed raise and lower the eigenvalues of

and similarly,

Combining these results, we see that

with

Restricting the Eigenvalues

To find the possible values of

First, we note that

so

Next, we can express

and similarly,

Adding these two expressions together gives

Therefore we have

which simplifies to

Since

As the norm term is non-negative, we have

We can add these two inequalities together to get

So this places a restriction on the possible values of

Plugging in

and plugging in

Solving these two equations simultaneously gives

We must have

The takeaway is this: if we have any eigenvector

This means that

Since

Substituting this back into the expression for

These results can be stated in theorem form.

The eigenvalues of the operator

where

We also need to address the normalization of the eigenvectors. We know that the eigenvalues of

Let's find the norm of the laddered eigenvectors. We have

Thus,

Substituting in the earlier expression for

We drop the phase factor by choosing

The action of the ladder operators on the eigenvectors

Let

We can find a closed-form expression for the eigenvectors

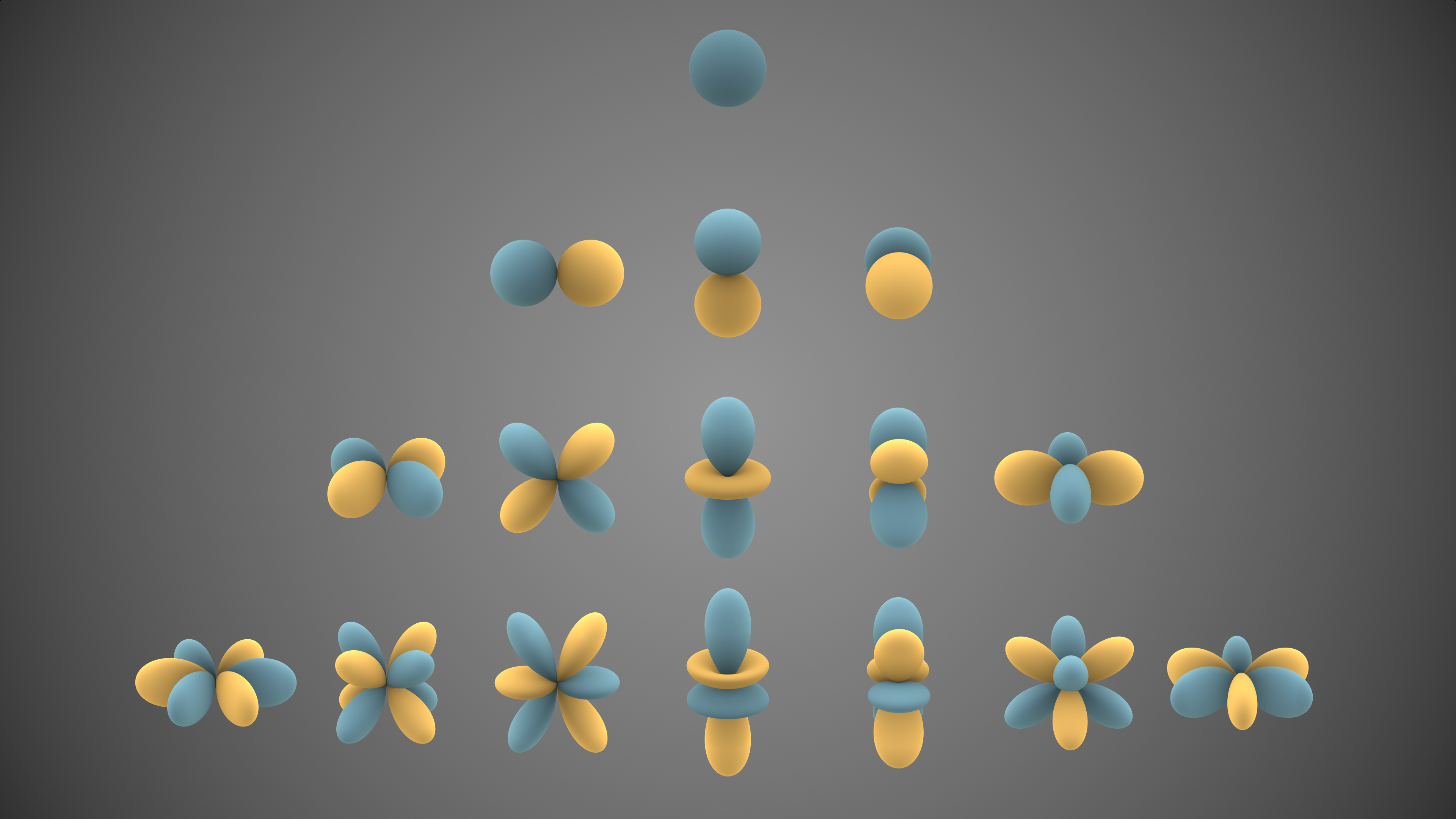

Eigenvalues of L² in Function Space (Spherical Harmonics)

Now we can return to the original problem of finding the angular part of the solution

Let's consider each component of the angular momentum operator in spherical coordinates. The eigenvalue equation for

Let's separate variables by assuming that

This is an ODE for

where

Integer Values of m

We will first consider the case where

We will need to find expressions for the ladder operators in spherical coordinates. Using the earlier expressions for

Recall that

This simplifies to

which is an ODE for

So the highest eigenfunction is

To find the rest of the eigenfunctions, we simply apply the lowering operator

It can be shown that applying the term in parentheses gives

So using that and

Repeatedly applying the lowering operator will lead to the general expression

where we have made the substitution

Finally, we can determine the normalization constant

This is just the Legendre polynomial

so we can use the normalization condition for Legendre polynomials to find

(the completeness relation for spherical coordinates), we have

Substituting

It can be shown that this leads to

Thus, the final expression for the eigenfunctions is

with

The

but for historical reasons, we use the associated Legendre functions defined by

We thus have

The spherical harmonics, which are solutions to the angular part of the Laplace equation in spherical coordinates, are given by

where

Appendix: L Only Depends on Angular Variables

To justify the step where we assumed that

Let

Let's convert this to spherical coordinates using the respective transformations

Using the chain rule, we have

Calculating the partial derivatives (using the transformations above), we have

Now we can use these expressions to rewrite

so

Similarly, for

so

Finally, for

so

Now we can compute

Similarly, for

And for

Adding these three expressions together, we have

In the last step we used a reverse product rule to rewrite the first two terms.

This final expression for